“Raise your hand if you’ve heard of the place, Birmingham,” prompted the facilitators. About a dozen sticky hands, skin every shade that you can imagine, sprinted into the air. “Who can help me out by sharing what you know about this place?” they continued.

One precious child, unable to contain her enthusiasm, quickly blurted out in a sing-song voice, “I don’t know where Birmingham is, but I know Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote a letter there from jail!” You might as well have knocked me over with a feather. We would go on to teach the history of the Children’s March to this crew, ranging from tots to teens, while their parents were downstairs learning nonviolent direct action skills. This was soon after Trump’s inauguration, my beloved EQAT’s way of observing Martin Luther King Day. Suffice it to say, I, too, had a lot to learn about Birmingham and the pivotal role it played in the Civil Rights Movement. In this post, mobilizing during a contested election and the behind-the-scenes prowess of Reverend Nelson H. Smith, Jr.

This fall, I’ve felt spiritually compelled to learn about the mechanics of the Civil Rights Movement – the strategic disputes, the less famous leaders, the campaigns that fizzled out, the early days when big splash moments were years away, a dream or a gamble at best. So learn I have done, pouring through interviews, archival documents, journalistic accounts, obituaries, footnotes, and more! And between and betwixt the headline moments, I’ve seen whispers of operations superstars everywhere. Who were these freedom fighters? What can contemporary changemakers and learn from our administrative ancestors?

As I read accounts of the Birmingham campaign, my eyes grow wide-as-saucers. I learned that the organizing effort was meticulously planned by Wyatt Walker, then president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC, Dr. King’s main organization). However, the plan was delayed twice because of the 1963 contested mayoral election. Ahhhhhh!

*checks calendar* *oh yeah, I almost forgot, the Trump/Biden election is TOMORROW*

This wasn’t just ANY election, nor any contested election. It was a confluence of factors (major egos, governance disputes, political pressure to end segregation) that took months of litigation to resolve. The premise of the contested election was “technically” about governance style. In an effort to finally give Bull Connor (cruel public safety commissioner of 22 year tenure) the boot, Birmingham’s politically ‘moderate’ intelligentsia class proposed amending the City Charter, moving from a commissioner to a mayoral governance model. This ballot measure passed in 1962, so of course, Connor ran for mayor in 1963 to continue his reign of power. When he was ousted by Albert Boutwell (by a mere 7,892 votes!), he contested the election (more specifically, the date of the handover of powers) and kept his commissioner-style of government meeting and adjudicating. So, two governments at the same time. One casually segregationist, the other staunchly (viscously) segregationist. Great. The case went all the way to the State Supreme Court, which unequivocally determined:

The trial court held the Mayor and Councilmen to be entitled to assume their respective offices, and the three City Commissioners were “prohibited from further use or usurpation or intrusion in purporting to act as Commissioners of the City of Birmingham.”

See Court proceedings here.

My interpretation of the judgment above is, “Get the hell out of here, ya losers!”

With an election, a runoff election, TWO mayor administrations, and (I would assume) widespread confusion about who was in charge, and (I would venture) massive resources and misinformation campaigns going to the electoral cycle, civil rights leaders faced an impasse. Continue with the Birmingham Campaign or delay for a THIRD time?

I learned in Parting the Waters, an uber-detailed and juicy account of the Civil Rights Movement from 1954-1963, that James Bevel is most responsible for turning the tide in Birmingham and forging ahead despite political uncertainty and dwindling turnout at the demonstrations. There’s a famous scene where Dr. King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy decide to violate the protest injunction, ending up in jail. While they are behind bars (writing letters and such!!), it’s Bevel and other civil rights leaders who continue to mobilize, innovate, and ultimately win. There are some wonderful stories to tell about the campaigning that ensued (look up The Children’s Crusade to learn more), but that is perhaps for a different blog post. For today, I’m writing all of this background because (1) I want us to know our history and (2) I’m setting up for a “big” reveal of a behind-the-scenes leader who deserves the spotlight.

Prior to his arrest, Dr. King had embarked on a “networking” campaign with the Birmingham elite:

[…] in an effort to appear as a unified black community. Included in the meeting[s] were Shuttlesworth, N.H. Smith, A.D. King, local Hendricks and W.E. Shortridge from ACMHR [Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights]; along with Dr. King, Abernathy, Andrew Young, James Lawson, Wyatt Walker, and Dorothy Cotton of the SCLC. Also in attendance were A.G. Gaston, Arthur Shores, John and Deenie Drew, Dr. Lucius H. Pitts, Reverend John Thomas Porter, Harold Long, and C. Herbert Oliver representing the city’s black middle class. The purpose of the committee would be to manage campaign policy and later assist with negotiations between the ACMHR-SCLC, white businessmen, and policy makers. In reality, the Central Committee was symbolic, a peace overture to the black middle class to project an image of racial solidarity. It allowed for the black middle class to involve themselves in the movement in a bureaucratic manner, even though the committee had no political power.

Gisell Jeter-Bennett, “We’re Going Too!” The Children of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement

Ph.D. dissertation, source here

Why name all of these names? I think it’s important to remember that there were LOTS of regular people who participated to varying extents in campaign deliberations. This is not the mainstream narrative! Of course it isn’t – if it was, it would be long, boring, and full of false starts (LIKE REAL LIFE!!). And perhaps most of all, it serves the status quo to treat activists like once-in-a-generation geniuses, rather than regular people acting on their values and trying to figure shit out.

Sure, we can poo-poo those people for being moderates or political props (there’s certainly a long tradition of that) (see Dr. King’s well-deserved scathing critique of white moderates in Letter from Birmingham Jail), but when we do that, I think we risk alienating near allies AND true members of the movement who are struggling with impostor syndrome… who feel like they aren’t a “real” activist, or who feel like whatever they are doing is not enough.

One of the big, conventional lessons of the Birmingham Campaign was to organize youth to (1) appeal to their risk-taking sensibilities; and (2) dramatize injustice. I couldn’t agree more – this was smart, powerful, visionary organizing.

But this isn’t the lesson that *I* took from my studies. What I learned when I went looking into history’s nooks and crannies was:

Scaling the Movement, rooted in broad vision and deep values, despite a contested election, ultimately led to big results

Under the surface was a broad coalition of regular people AND organizations with clear systems and strong infrastructure

Behind and within the SCLC and SNCC were archivists, journalists, historians, secretaries, hosts/hostesses, drivers, printers, and all kinds of people who worked on logistics. One person who I want to highlight is Reverend Nelson H. Smith, Jr. I think he is seldom remembered because he was usually second fiddle to Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, who had a fiery personality. In one source (okay, Wikipedia), Shuttlesworth is described as,

combative, headstrong, and sometimes blunt-spoken to the point that he frequently antagonized his colleagues in the Civil Rights Movement as well as his opponents. He was not shy in asking [Dr.] King to take a more active role in leading the fight against segregation and warning that history would not look kindly on those who gave “flowery speeches” but did not act on them.

source

Knowing his reputation, I was immediately intrigued when I saw that the Birmingham Manifesto, released in April 1963, had two signatories: Shuttlesworth and Smith. Who was this N.L. Smith? What did it mean to be Secretary of ACMHR? (Lest we fall into the trap of pitting two Black men against each other, I want to say that I think they BOTH deserve to be remembered and honored in the annals of Civil Rights Movement history).

So, as you all kept on text banking and phonebanking in the wee hours of election eve (THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU!), I went digging. What what I found was a fascinating and humble interview transcript with none other than Rev. N.L. Smith, himself. The interviewer pushed for… shall we say … gossip about Smith and Shuttlesworth and their different theologies and leadership styles. Read on if you want to learn more about whether a church should be run like a democracy (or not) — it’s really wonderful!

Sprinkled within this animated discussion were some pointed questions about Reverend Smith’s role:

REVEREND SMITH: I was the secretary. Kept the records.

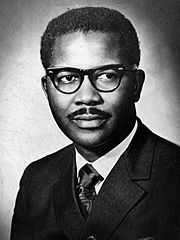

Reverend N.H. Smith, Jr.

ANDREW MANIS: Of which meetings?

REVEREND SMITH: Well, mainly the board meetings but I took the lead in getting […] we would catalog the people who would join and get the membership cards out and this kind of thing, the announcements, you know, just the general functions that a secretary would have to do. That’s what I did.

interview c/o Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (link here)

Try as I might, I could not find (yet?) digitized board minutes from ACMHR meetings, but I did get to read some from other organizations which only wet my appetite to keep this project rolling! So… stay tuned… there’s more to come!

But what I found especially touching about Rev. Smith’s interview is his deep commitment to servant leadership and to doing whatever it takes, even if it’s not glamorous. Twice in the interview did he mention circulating membership cards! What a quaint, concrete, administrative, crucial component of behind-the-scenes work!

The interview is briefly interrupted, but ends with this emphatic quote:

They can’t tell me that lie because the first meeting in June. I kept the records. I know who came to the Movement. I know who carried a card because I signed it. We used to meet over here on Beta Street, 309, using Roberts house and work until the wee hours of the morning getting out those cards. I know who showed up at those meetings. [goes on to defend Fred Shuttlesworth’s character].

Reverend N.H. Smith, Jr.

interview c/o Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections (link here)

I write this as someone who tried (and failed) to administer a database system for keeping track of memberships. As someone who has rooted for database-changemaker-leaders who are developing an open source model for managing memberships in Salesforce because it is so, damn, complicated!! Payments, renewals, refunds, affiliations, benefits, delicate relationships, and much, much more had to be tracked diligently despite real life changing circumstances all the time. Even consistently tracking attendance at Zoom meetings is something that groups I work with have struggled to do. Paper? Spreadsheets? Database system? Is it even worth it? It’s time consuming and it’s so often considered a sideline to the “real work” of social change.

It’s clear to me from Rev. N.H. Smith’s stories that he saw this work as woven into the cycle of “meeting, marching, and mail-merging” (as I like to say) and I invite you to do the same!

It’s not every day that we get glimpses into the folks who did this work for the Civil Rights movement, and so when we do, I think it’s really important to savor them.

So, to my dear dear Election Defenders out there, and changemakers far and wide, if you’re reading this, I honor each of you for your organizing and administrative-logistical prowess, for the follow-up, registration logging, “democracy pod”-building efforts that most people will never see. If you are up late into the night doing a modern day equivalent of signing membership cards to prepare for the struggle, I see you, and this one is for you.

I am loving these posts!!! Thank you for doing this work & educating us all!